Phocaea burning, June 1914. Photos: Félix Sartiaux.

The pillage of Foça (Gr: Φώκαια, Phocaea) and the massacre of over 100 Greeks in June 1914 was committed during the early phase of the Greek Genocide. While the death toll by direct killing was on a relatively small scale, the plan to force Greeks to flee en masse was accomplished. The massacre and looting resulted in the mass expulsion of the Greeks of the town and coincided with over 100,000 Greeks from the surrounding region abandoning their homes and seeking refuge in Greece and the neighboring islands due to similar measures.

The pillage and massacre at Foça was part of a wider policy to rid the Aegean coastline of Asia Minor of its vast Greek communities. The policy was put in place by the CUP (Committee for Union and Progress) political party as early as 1913 in the regions of Thrace and continued in the region around Smyrna in 1914, before the start of the First World War.

The location of the massacre was Eski Foça (Old Phocaea) situated some 50km north-west of Smyrna (today Izmir) and approximately 15km south of Yeni Foça (New Phocaea). At the time, Eski Foça had a population of 8,000 Greeks and about 400 Turks.1 The massacre began on the night of the 12th of June when armed irregulars (Boshibozuks) who had earlier looted towns south of Menemen, attacked the town. The massacre lasted 24 hours. The eyewitness testimonies of Frenchmen Monsieurs Manciet and Sartiaux have provided the most detail in describing the sequence of events surrounding the massacre. Manciet recounted the events as follows:

During the night, the organized bands continued the pillage of the town. At the break of dawn there was continual tres nourrie firing before the houses. Going out immediately, we four, we saw the most atrocious spectacle of which it is possible to dream. This horde, which had entered the town, was armed with Gras rifles and cavalry muskets. A house was in flames. From all directions the Christians were rushing to the quays seeking boats to get away in, but since the night there were none left. Cries of terror mingled with the sound of firing. The panic was so great that a woman with her child was drowned in sixty centimetres of water.2

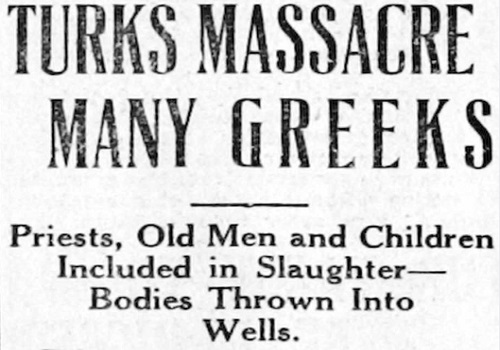

Turks Massacre Many Greeks. Ogden Daily Standard, June 16, 1914, p.1. Source

Félix Sartiaux (1876-1944) was a qualified engineer and archaeologist who was sent to Asia Minor by the French Government in 1913 to conduct archaeological excavations at the ancient town of Eski Foça. Around 600BC, the French city of Marseille was founded by Greek seafarers of the town. On his second visit to Foça in 1914, Sartiaux witnessed the entire 24 hour pogrom, took photographs and recorded testimonies from survivors. His testimony was published in 1914 under the title Le Sac de Phocée: et L'expulsion des Grecs Ottomans d'Asie-Mineure en Juin 1914.

On the day before the massacre (11 June), while excavating just outside of Foça, Sartiaux witnessed people in a heightened state of fear fleeing towards the town. They were Greeks whose towns had been raided by Turkish irregulars and who were now escaping to the sea or seeking asylum in Eski Foça.

With an attack on the town imminent, Sartiaux and his colleagues sought protection from the kaymakam (the local Governor) who offered to shelter them in his own residence. The Frenchmen refused the offer and declared to him that if anything happened to them, he would be responsible. They were however given a gendarme (policeman) to protect their houses. The Frenchmen hastily created four French flags and hoisted them on their houses. The doors were kept wide open and during the sack of the town, some 700-800 Greeks gathered at the houses and were saved from attack. Sartiaux described the massacre as follows:

Just as our homes are being emptied of refugees from the previous night, they begin filling again with new arrivals who feel secure from the violence, only under our roof. Their lives have been saved due to the sole fact that they abandoned everything and fled. The majority are wearing torn clothing many of them are covered in blood. Due to the ferocity of the assault, they were not even able to take some bread with them for the road. Wealthy notables from the region fled bare-footed, the bandits even taking their shoes. The children cry as they search for their parents. We don't reveal to a mother that her two children have been murdered. We find a newborn child on the street but we are unable to find its mother so we give it to another woman who is breastfeeding her own child. Women approach us in desperation and beg us to find their husbands or their fathers, or their daughters who were raped or abducted.3

Alfred van der Zee was the Danish Consul at Smyrna at the time. He quoted an eyewitness as saying:

Within half an hour after the assault had begun, every boat in the place was full of people trying to get away, and when no more boats could be had, the inhabitants sought refuge on the little peninsula on which the lighthouse stands. I saw eleven bodies of men and women lying on the shore. How many were killed I could not say, but trying to get into a house of which the door stood ajar I saw two other dead bodies lying in the entrance hall. Every shop in the place was looted and the goods that could not be carried away were wantonly destroyed.4

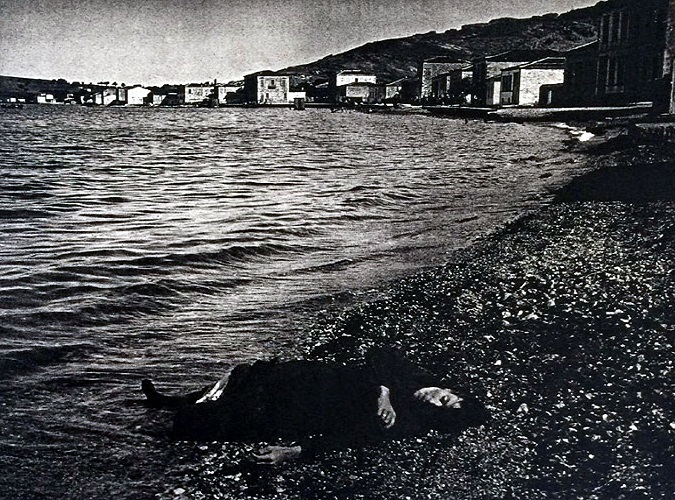

The body of a deceased female. In the background Turkish chettes are entering the town. 13 June 1914.

According to Archimandrite Alexander Papadopoulos, and based on official reports, the massacre at Foça was planned by the Commander of the Gendarmes of Menemen, the infamous brigandTalaat. Others implicated were the Lieutenant of Police in Eski Foça, the director of the salt-works Ali Bey, the inspector of the tobacco monopoly Ibrahim Effendi, the Commissioner and former Mufti Serres Bey, the Mayor Hassan Bey, the municipal physician Saim Bey, Nadir Bey, Hassan Ali Parmak and others.

According to the reports, all the shops were plundered and sacked, and all the houses were robbed and stripped bare. The church of Saint Eirene was plundered and its altar desecrated. The attackers climbed the belfry and threw the cross to the ground after which a muezzin (Turkish preacher) sang a hymn of thanksgiving in honor of the conquest of the town. Heinous acts committed included butchering and slaying ‘like a lamb’ of men, women and children, cutting off of women's breasts before killing them, the choking to death of children, throwing victims into wells, abductions, hangings and rapes. Many fled to the surrounding hills to escape the massacre.

The Christians of Yeni Foça suffered the same fate as those from Eski Foça. A steamer had been sent to search for those who were missing following the massacre and 52 women were found on the nearby barren island Peristerou simply awaiting death by starvation. Near Eski Foça, 20 desperate Greeks were found in a cave and holes in the ground. At Saltza which lies halfway between Eski and Yeni Foça more than 400 men, women and children, inhabitants of Yeni Foça were found in frightful desperation.5

According to Kuscubasi Esref an SO (Special Organization) leader, the cleansing of the Greeks of the Aegean region of Asia Minor was planned. Esref quoted Enver Pasha (Minister of War) as saying on Feb 23, 1914 that non-Muslims had to be got rid of because they did not support the continued existence of the state and that the salvation of the state was linked to stern measures against them.6 French eyewitness Manciet recounted: “All the evidence points to this having been an organized attack with the purpose of driving from the shores the Rayas, or Christian Ottomans.” Likewise Sartiaux identified two local CUP members as orchestrators of the pillage.

The massacre at Foça resulted in large numbers of Greeks fleeing to the Foça shoreline seeking urgent passage out of Asia Minor. Some 700 Greeks were able to flee on a French steam tug boat which transported them to the island of Mytilene. The authorities at Mytilene then sent boats to rescue a further 5-6000.

Following the Ottoman Empire's defeat in the First World War (Nov 1918), many Greeks of Foça who fled in 1914 returned to their homes, as did Félix Sartiaux. These Greeks were expelled again, being forced to flee in 1922 following the Hellenic Army's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War.

Greeks who fled Foça settled primarily in two regions on the Greek mainland and today these two regions have been named after Phocaea. One is Nea Phocaea in the Halkidiki region of northern Greece and the other Palaia Phocaea in the Attica region of Greece, south of Athens. In 2010, a street was named in honor of Félix Sartiaux in Nea Phocaea, Halkidiki paying tribute to his brave act in providing protection and refuge to 800 Greeks during the massacre. A monument was also erected in his honor.

Turkish irregulars showing off their booty after the pillage of Phocaea. At the head, a Turkish bandit shows off an umbrella, while in the background the French flag flies on top of a house as Greeks gather along the quay seeking passage out of the town. Photo: Félix Sartiaux.

1. George Horton, The Blight of Asia. Sterndale Classics UK, p 28.

2. ibid p28.

3. Félix Sartiaux, Phocée 1913 - 1920; Le témoignage de Félix Sartiaux. Kallimages, p 215.

4. Matthias Bjørnlund, in Late Ottoman Genocides: The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and Young Turkish population and extermination policies. Routledge, p 40.

5. Archimandrite Alexander Papadopoulos, Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey before the European War. Oxford University Press 1919, pp 124-125.

6. ibid ^Matthias Bjørnlund, p40.

Further Reading:

16 Jun 1914: Massacre of 100 Greeks in Asia Minor, The Daily Telegram

The 1914 cleansing of Aegean Greeks as a case of violent Turkification.

Le Sac de Phocée: et L'expulsion des Grecs Ottomans d'Asie-Mineure en Juin 1914.

Phocée 1913 - 1920; Le témoignage de Félix Sartiaux.

Félix Sartiaux: An Eye-Witness to the Massacre of Greeks at Foça