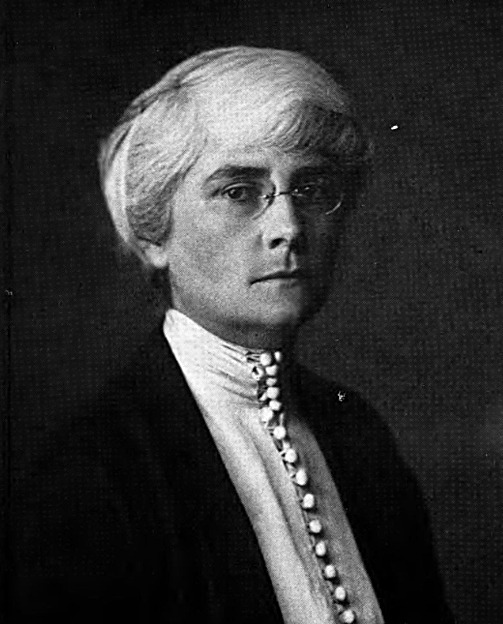

Dr. Mabel Evelyn Elliott. Source: Drexel University College of Medicine

Mabel E. Elliott (1881-1968) was an American physician who cared for Greek and Armenian refugees and orphans during and after the Ottoman-era genocides. Some of Elliott’s most significant work was conducted at Marash (today Kahramanmaraş), Nicomedia (today İzmit), Yerevan and Greece.

Elliott was born in London, England in 1881 and moved to the United States with her family in 1883 where she grew up in St. Augustine and West Palm Beach, Florida. In 1904, she and her sister Grace Papot were among the first women to graduate with degrees from the Rush Medical College in Chicago.

Elliott was one of eight physicians selected by the American Women’s Hospitals Service (AWHS) for duty with the Near East Relief (NER). She sailed with a large group of relief workers on the USS Leviathan in February 1919 and arrived in Constantinople (today Istanbul) early in March.1

Her first call of duty was in Kahramanmaraş where in May 1919, she set up and directed a three-storey hospital caring for Armenian refugees who had survived deportations and massacres during the genocide. Following WW1, Kahramanmaraş had come under British then French occupation. In January 1920, the Kemalists attacked the French forces and committed a massacre of 12,000 Armenians resulting in a French retreat. The following month, French authorities ordered relief workers to leave. Elliott led her staff along with thousands of refugees in freezing conditions over snow-covered mountains to the safety of Adana. Following her ordeal, she returned to Benton Harbour, Michigan to recuperate and resumed her practice of medicine.2 In 1924, she published Beginning Again at Ararat (Fleming H. Revell Company) detailing her personal experience during the 1920 battle of Marash and the plight of Armenians and Greeks in the Near East.

In the Autumn of 1920, the executive board of the AWHS appointed Dr. Elliot head of the AWH service in near eastern countries and sent her back to Constantinople with other personnel as director of the operation. She returned to Turkey in October 1920 and took over the medical work of the NER at İzmit, Derince and Bahçecik (Arm: Bardezag) and was stationed there between January and August 1921. İzmit was occupied by Hellenic and British forces at the time and a large number of Christians had accumulated there after fleeing massacres by Kemalist forces in outlying villages. Dr. Elliott was stationed at İzmit with Mrs Mabel A. Nickerson and in a letter received by the AWHS dated March 31, 1921, they wrote:

We have refugees all the time from across the gulf where the Turks are up to their usual pastime of massacring the Christians. Twenty-six came in from a village the other day, and they were all who had escaped the knife. We watched the flames reach to the heavens as the poor little homes were laid in ashes.3

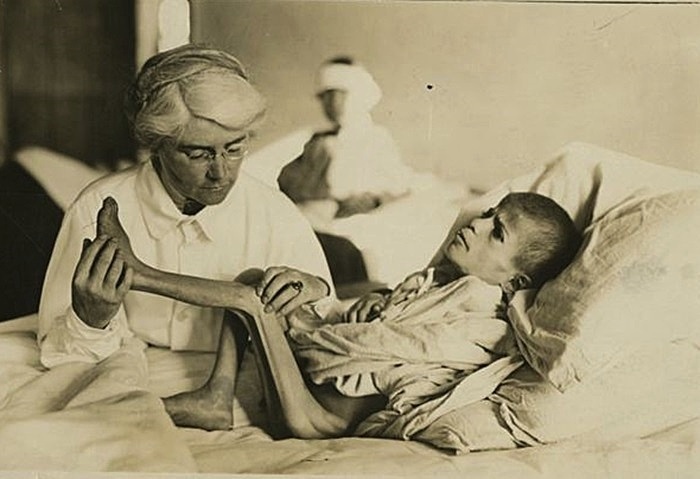

Health conditions in the area were extremely poor with those fleeing massacres and many children dying in camps from deprivation and disease. On March 14, 1921, they wrote:

I wonder if the people in America realize what the magic words “American Women’s Hospitals” mean to these people out here?… Many of the children are brought to us with their knees drawn up to their chins. They have lain such a long time in this position trying to keep or get warm, that it takes days of oil rubbing to loosen up the tendons sufficiently to draw their legs down straight. Many of them die within a few hours after their arrival, but usually if we can get them over the strain of the first two or three meals, they gradually begin to take a little interest in life and it is a wonderful satisfaction to see them slowly get a grip on life and learn to smile.4

Dr. Mabel Elliott examining a young boy (c.1921). Source: Drexel University College of Medicine

In June 1921, with over 30,000 refugees crammed into İzmit, the Hellenic military decided to abandon the region, taking with them all the refugees. Following this, in August 1921, Elliot was transferred to Yerevan in Armenia to take over the medical work of the Near East Relief in that region.

However, following the holocaust at Smyrna in September 1922, the AWHS was again called to provide relief to survivors of massacres and those fleeing or being expelled from Turkey. Elliot initially went to Rodosto (today Tekirdağ) in Eastern Thrace to inaugurate medical work for the thousands fleeing Turkey. Then, in the first week of October, she arrived at Mytilene on the island of Lesbos which was overflowing with almost 200,000 refugees fleeing the Smyrna massacres and established a medical relief service including hospitals, clinics and milk stations. During the same month, she was on the island of Chios doing similar work. In a letter dated October 9, 1922 she wrote:

When we reached Mytilene practically nothing was being done for the care of the refugee sick. The wretched municipal hospital was crowded to the doors, and people on all sides begging and praying for help. The sick were lying in the streets, and women giving birth to babies in the open places without help or protection. Thank Goodness! Today we have a hundred-bed hospital, where maternity cases are given first place.5

In October 1922, Elliott arrived in Athens and was made head of the American Women’s Hospitals in Greece. Between November 1922 and August 1923, she supervised all the work of the AWHS in Greece including operations with other relief organizations such as the Near East Relief. She established the Pireaus Hospital which operated with tents in the backyard and in December, established three clinics in Crete where there were 55,000 refugees. She also helped establish twelve orphanages which were caring for 10,000 orphans throughout Greece and the islands and a maternity hospital in Thessaloniki.

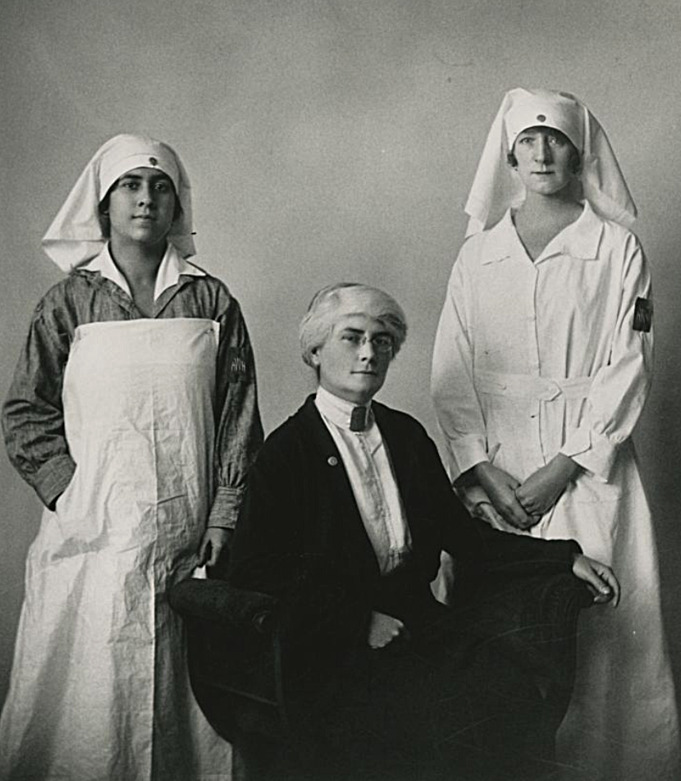

Dr. Mabel Elliott with an English nurse and a refugee who became a nurse for the AWHS. Greece, c. 1922. Source: Drexel University College of Medicine

In a cablegram from Athens dated Nov 23, 1922 to AWHS headquarters, Elliot highlighed the worsening conditions in Greece and made a plea for funds from the American people. She wrote:

Serious as pictures of situation in refugee camps months ago, things have steadily worsened since that time. If American people are really interested in welfare [of] these refugees, time to help on large scale has now arrived. Such emergency work has been done thus far has been good but thousands are going to die unless more American help..[...] I find myself forced everyday forced [to] provide more than mere medical care for women children who lie on bare ground[...]

Situation terrific beyond words and we see no hope for real solution unless American people willing to undertake leadership on wide scope within next month. World at large apparently not yet comprehends that here are million refugees almost totally without men. They are all women, children and can't [be] expected [to] shift for themselves. Is there no way bringing American people to realize how much these helpless hapless folk need their assistance.6

With health conditions deteriorating and quarantine stations unable to cope with the steady influx of refugees from Turkey, in early January 1923 the Greek government temporarily halted the entry of refugees into the country and decided to use the uninhabited island of Macronissi off its coast as a quarantine facility for the thousands who were arriving on ships, most of them women, children and elderly. Nearly all on board were exposed to typhus and smallpox. The AWHS, under the charge of Dr. Elliott, was called to take on the responsibility of establishing a quarantine station and to conduct the entire medical work associated with the exercise. Dr. Elliot wrote:

A few nights ago, Mr. [Asa] Jennings rushed in and said, “Doctor, you’ve got to do something about this, you know you always help us out. What can the American Women’s Hospitals do about this ?”—And the next morning, we went over to the Island of Macronissi… That afternoon, I decided to open a quarantine station, and that night I ordered the tents and blankets and got to work.7

Dr. Lovejoy, Mr. Moffat, and Dr. Elliott at Macronissi. Source: Drexel University College of Medicine

In total, 12,295 refugees were received on the island and were kept from one to four months. They were all vaccinated, fed, clothed and finally transferred to mainland Greece.

Elliott’s work in Greece did not go unrecognized. In March 1923, the Greek Minister of Housing and Public Hygiene Mr. D. Doxiades wrote a letter to the AWHS and stated:

I have the honor to express to you by this letter the gratitude of the Greek Government and the Greek Nation as well as the thanks of more than a million refugees for your admirable effort in medical and hospital work in favor of those suffering crowds driven away from their homes.

Your organization, represented in Greece by Dr, Esther Lovejoy and Dr. Mabel Elliott, has really been at the height of a very difficult situation. The great help which you offer to the Greek Nation in this critical period, when we had to accept into our country hundreds of thousands of unhappy refugees driven away from their homes by the Turks, will remain for ever engraved in the heart of us all.8

Hospital pavillions and disinfecting stations on Macronissi island. Source: Drexel University College of Medicine

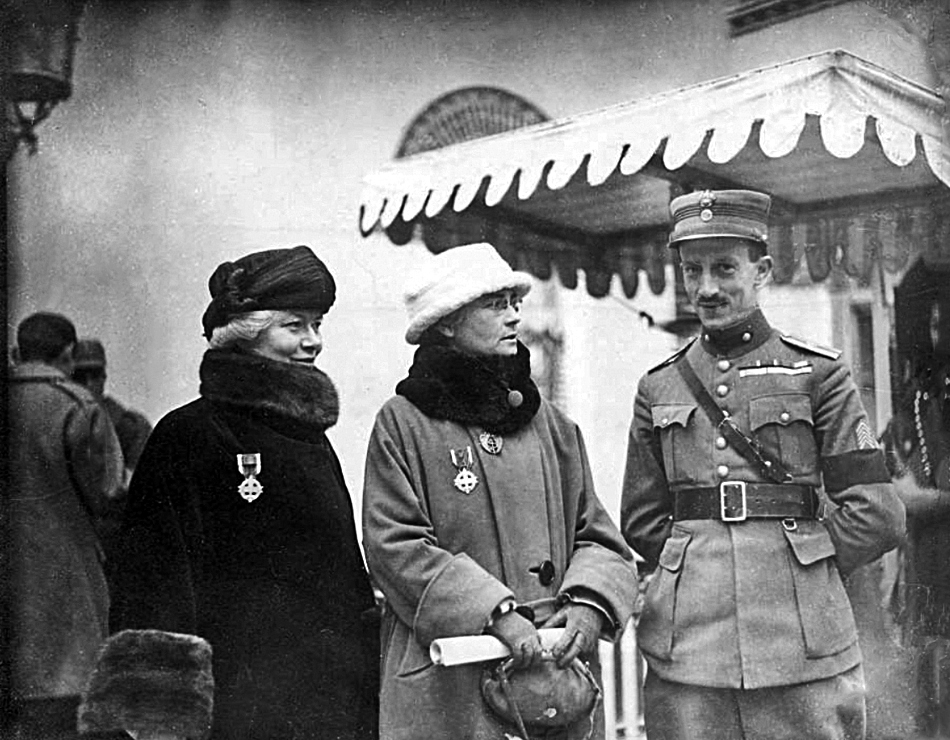

In February 1923, the Greek Government awarded Dr. Elliott the Greek War Cross for her work in caring for the refugees and orphans in Greece.9 It was the first time a woman had been awarded the medal. However, in July of that year, Elliott resigned her position as director of medical work in Greece citing persistent interference of certain members of the New York governing body in the local administration of relief work and she returned to the U.S.10

In 1925, Elliott was selected to lead the public health department of St. Luke's International Medical Center in Tokyo, Japan. She remained in Japan until 1941. She died in West Palm Beach, Florida in 1968, at the age of 87.

Elliott's life is chronicled in a book titled Unbreakable Healer (Palmango 2025).

Dr. Elliott (middle) after being awarded the Greek War Cross in 1923. Source: Findagrave

1. Lovejoy, E. P. Certain Samaritans. The Macmillan Company, New York, 1927, p. 73.

2. Certain Samaritans, p. 83.

3. Certain Samaritans, p. 85.

4. ibid, p. 85.

5. ibid, pp. 174-175.

6. Nov 23, 1922. Cablegram, Athens 270/269 accessed at https://doctordoctress.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A1492

7. Certain Samaritans, p.196.

8. ibid, pp. 275-276.

9. Feb 16, 1923. War Cross for Women. The Harlem News, p.2. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86075250/1923-02-16/ed-1/seq-2/>

10. July 23, 1923. U.S. Official Resigns Athens Post. The Evening Star, Washington, p.13. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1923-07-23/ed-1/seq-13/